By Andrew Yamato and Alan Flusser

People don’t generally give pockets much thought. Even our clients, commissioning every detail of their jackets, often don't have particularly strong feelings on the subject. Fortunately for them, we do! Functionality aside, the pockets on a suit jacket or sport coat are aesthetically prominent elements that should be carefully considered using the basic criteria of type, shape, and placement.

Type

There are two basic types of pocket — besom and patch — each of which may be with or without flaps. Besom, also known as jetted pockets (named after the long narrow beads of fabric which define the edges of the pocket opening) are cut into the front of the coat, with the actual pocket bag falling between the cloth and the lining. When cut with flaps, they are appropriate for both suits and sportcoats. Besom pockets sans the flaps are a bit more streamlined and thus more dressy. They are de rigeur for the dinner or tuxedo jacket, which, incidentally, should never carry a flapped pocket.

Below are a couple formal jackets with besom pockets — a black tuxedo jacket with grosgrain trim and an alternative dinner jacket.

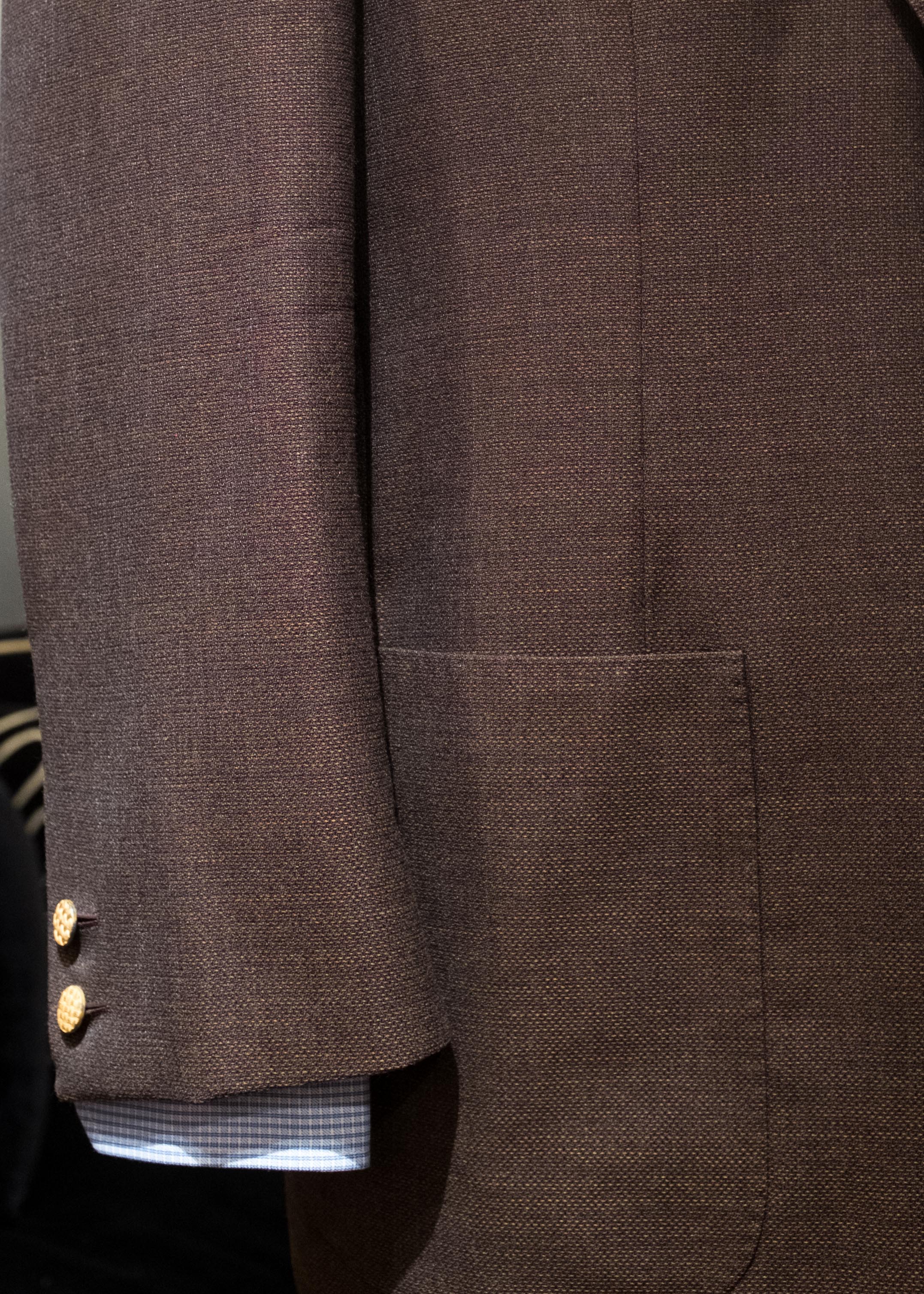

Patch pockets are fashioned by attaching the separate pocket to the coat’s front. The added bulk and visual interest of this simpler technique gives a garment a more casual feel and is most appropriate for sportcoats, but can also lend a quirky element to a more casual suit or traditional blazer, which tones down the formality of the garment. Patch pockets can be plain or pleated for extra capacity and drama. Beyond that are the gusseted “bellows” variety sometimes seen on tweed shooting jackets for ammunition portage.

Below, patch pockets on a brown wool hopsack blazer, and on a wool and silk seersucker slack jacket.

Shape

Shape is a consideration for patch pockets, and can dramatically affect the overall personality of a garment. Savile Row cutters traditionally cut more or less quadrilateral patch pockets that reflected the relatively squared front edges of their coats, while Neapolitan tailors favored more asymmetrical, curvaceous shapes that complemented their rounded cutaway fronts. Our aesthetics dictate that the patch shape mirror the lines of the coat, so our patch’s outside line is more curved while its inside is slightly more squared off. As neither is parallel to the other, this makes for a somewhat off-beat, imperfect, hand-made looking affair….. just the way we like it.

With besom pockets, the shape in question is that of the flaps, and the design of our pocket flaps is intended to echo and therefore harmonize with the coat’s front, rounded for the single-breasted’s cutaway and curved front, a ninety degree corner for the double-breasted’s squared-off front. (see photo examples below). Besom pockets are most often cut horizontally, but a slightly more custom-y touch is to take a page from equestrian style and angle them back slightly for a bit more rakish look.

On to the breast pocket – much like a jacket’s shoulder expression, lapel shape, or waist button position, the breast pocket is a dead giveaway as to its taste and design bonafides. Since breast pockets are designed to accommodate a pocket square, if they are not angled slightly out and upwards that’s not good; and if placed high on the chest, that’s even worse! Alternatively, at the top of the tailored pocket-as-art mountain of minutia sits the curved welt breast pocket known to the Italians as barchetta (or “little boat”) — which follows the curvature of the chest and provides the best chance for the effective staging of a pocket square. When function and form in a tailored garment do manage to meet up, it’s usually a good time for all.

The sharp corners of these pocket flaps complement the squared front edges of this double-breasted suit jacket.

The curved front edge of this single-breasted suit jacket is reflected in the rounded front corner of the pocket flaps.

Placement

No matter how beautifully executed, pockets can ruin the effect of a garment if they are incorrectly placed. Given how significantly the front expanse of a coat can vary from one pattern to another, knowing how to avoid this is largely a matter of having a good eye guided by good taste. Hip pockets placed too high will truncate a man’s torso, while placing them too low imparts a droopy effect. Breast pocket placement offers a bit more stylistic latitude, but we believe that a traditional, slightly lower position confers a more relaxed elegance.

The same with patch pockets — sitting too high on a jacket will undermine one of its principal raisons d’etre – to project a casual, throwaway chic. A soft, drapey effect cannot be achieved if the hip pockets are stationed too far from the coat’s bottom or so high on its chest that they appear to pull the coat upwards off the back, instead of downwards and forward. The man should look like he’s wearing the coat, not the other way around.

Below, the top of the ticket pocket anchors the waist, with the lower pockets settling appropriately beneath. The chest welt pocket hangs just a bit lower than commonly seen today.

The Ticket Pocket

No discussion of jacket pockets is complete without mentioning the enduring appeal of this little vestigial detail left over from the modern suit’s origins. Positioned above the right hip pocket and about two-thirds its width, the ticket pocket is also known as a change or cash pocket, and was originally intended to provide mounted gentlemen with easy access to money for tips and tolls. Their use later expanded to stowing train ticket stubs, and they’re very useful for keeping keys safe yet handy.

We’re fans of ticket pockets, seeing them as a subtle connection to the history of menswear and offering an interesting custom touch, but as with every other detail of a coat, a ticket pocket should exist in harmony with the rest of the garment. They tend to look best on taller folks, for whom they can help break up the expanse of the right side of the coat and balance the left breast pocket. Shorter clients might want to steer clear of them since they can look cramped or cluttered on shorter jackets.

The Elegance of Utility

Ready-to-wear coats are often sold with their pockets sewn shut, which unfortunately prevents some wearers from realizing that they’re even functional. Some men elect to keep them this way to prevent their pockets from sagging. This is of course a matter of preference, however let us weigh in as we are apt to on most matters sartorial. You are not marble and clothes are not meant to look like sculptures, so forget this practice – it’s precious and silly.

Go ahead and thrust your hands into your pockets as you saunter down a street: that’s exactly the sort of quotidien elegance that made Fred Astaire such a style icon. Good clothes are meant to be lived in, broken in, and none the worse for showing it here and there.